Original Article

Volumen 9, Número 17/Enero-junio 2026

Percepciones de los estudiantes sobre la inteligencia artificial en el aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera

Brayan Fernando Artunduaga-Sánchez

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-0244-3438

Master’s student in Education at Universidad de la Amazonia. Specialist in Pedagogy, Colombia.

Paola Julie Aguilar-Cruz

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8386-9104

PhD (c) in Education and Environmental Culture; Master in Education; Specialist in Pedagogy. Teacher and Researcher at Universidad de la Amazonia, Colombia.

Julián David Mejía-Vargas

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-1294-1376

Master in Education. Professor of Applied Linguistics and English Literature at Universidad de la Amazonia, Colombia.

ISSN 2619-2608

DOI: https://doi.org/10.34069/RA/2026.17.01

Cómo citar:

Artunduaga-Sánchez, B.F., Aguilar-Cruz, P.J., & Mejía-Vargas, J.D. (2026). Students’ perceptions of Artificial Intelligence in EFL learning. Revista Científica Del Amazonas, 9(17), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.34069/RA/2026.17.01

Recibido: 31 de octubre de 2025 Aceptado: 2 de febrero de 2026

Abstract

This article aims to describe 10th-grade students’ perceptions of the use of Artificial Intelligence in English Language Learning. Using a mixed-method design, data were collected from 159 students through surveys and from 10 students through semi structured interviews. The findings reveal that students reported positive experiences, appreciating AI’s immediacy, accessibility, and motivational potential. However, they also identified limitations such as inaccurate responses, internet dependence, and reduced creativity when overusing these tools. The results also highlight a gap between students’ independent use of AI and its limited presence in formal classroom instruction. In addition, students expressed the need for teachers to guide them in using AI ethically and effectively. Overall, the study emphasizes the importance of developing AI literacy and critical awareness in English as a Foreign Language education.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, english language learning, student perception, education.

Resumen

Este artículo tiene como objetivo describir las percepciones de los estudiantes de grado décimo sobre el uso de la Inteligencia Artificial en el aprendizaje del inglés. Utilizando un diseño de método mixto, se recopilaron datos de 159 estudiantes a través de encuestas y de 10 estudiantes mediante entrevistas semiestructuradas. Los resultados revelan que los estudiantes reportaron experiencias positivas, valorando la inmediatez, accesibilidad y el potencial motivacional de la IA. Sin embargo, también identificaron limitaciones como respuestas inexactas, dependencia del internet y una reducción de la creatividad cuando se hace un uso excesivo de estas herramientas. Los resultados también evidencian una brecha entre el uso independiente que los estudiantes hacen de la IA y su presencia limitada en la enseñanza formal en el aula. Además, los estudiantes expresaron la necesidad de que los docentes los orienten en el uso ético y efectivo de la IA. En general, el estudio enfatiza la importancia de desarrollar la alfabetización en IA y la conciencia crítica en la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera.

Palabras clave: Aprendizaje del inglés, educación, inteligencia artificial, percepción de estudiante.

Introduction

The use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become widespread in the education setting, the field of English Language Learning (ELL) being not an exception. Students can use AI in this environment to access information and to actively acquire English language (Atencio-González & Criollo-Ñato, 2025; Robayo-Pinzón et al., 2023). Such new practices are transforming the usual nature of the ELL classrooms (Caiza et al., 2025; Guanuche et al., 2025), on the other hand, technology is no longer an additional supplement but a necessary element of the student’s self-learning process.

Although the use of AI in education is rapidly expanding, very few studies have taken place regarding the perception of AI-enhanced language learning tools to students. These perceptions are also essential to understand because they are likely to influence the confidence and readiness of students to use AI in ELL (Castillo-Cuesta et al., 2025; Davis, 1989; Nelson et al., 2025; Kessler, 2018). The attitude of students towards technology often dictates whether they will accept or decline the use of this kind of innovation, hence the need to clarify how they perceive and experience AI for ELL in educational institutions (Insuasty et al., 2025; Zambrano Rodriguez et al., 2025).

Though the research on the intersection of AI and education is growing in scholarly research, most of the existing studies considered the intersection in the higher education context (Acosta-Enríquez et al., 2025; Arbulú Ballesteros et al., 2024; De La Torre & Baldeón-Calisto, 2024; Vargas Bernuy et al., 2025; Vera, 2023) or on the perspectives of teachers (Aguilar-Cruz & Salas-Pilco, 2025; Bottiglieri et al., 2025). As a result, there is a significant gap as regards to secondary school students and especially the Latin American students regarding their attitudes and use of AI tools to learn English. To fill this gap, the following research question was formulated in this study: What are the perceptions of 10th-grade students in Florencia, Colombia, regarding the use of AI as a tool for ELL? Therefore, the study pursues three specific objectives: (1) to identify general knowledge and use AI tools by 10th graders, (2) to analyze 10th graders’ experiences regarding the integration of AI in their ELL process, and (3) to describe the perceived benefits and challenges of using AI for ELL from the perspective of 10th graders.

The article is organized as follows: in the first section it presents the theoretical framework, describing AI in language education and students’ perceptions. Later, it outlines the methodological design of the study. Then, it reports the main findings and discusses the implications of these findings for ELL. Finally, it presents the conclusions.

Theoretical Framework

Artificial Intelligence in Language Education

AI in education includes many types of smart tools, but the fast growth of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) has been notable and widespread. GenAI is a type of AI that can create content from scratch (text, picture, audio, video and more) by learning patterns from large amounts of data (Cabrera-Solano et al., 2025). Earlier AI tools mostly checked or classified information, like grading essays or finding grammar mistakes, but GenAI makes completely new content from user prompts (Dwivedi et al., 2023). Hence, GenAI works mainly through large language models like OpenAI’s GPT, XAI, Gemini, Deepseek, among others. These tools are trained using significant amounts of data; as a simple example, textual inputs allow them to produce grammatically correct and meaning-bearing sentences (Muñoz et al., 2025). Therefore, GenAI is an innovative tool in the educational setting especially in the language acquisition field.

This technology offers new possibilities to language learners: GenAI can generate reading passages with different levels of difficulty, demonstrate the natural conversation, imitate the real conversations, and even clarify to them the reasons why a particular utterance might sound more natural (Kohnke et al., 2023, 2025; Rojas-Paucar et al., 2025). Regardless of such benefits, GenAI implementation in schools creates some challenges. It also poses relevant questions about academic integrity and authorship and there is still a risk of bias in case the learners do not critically assess the produced information. The study habits can be transformed by GenAI positively and negatively (Andrade-Girón et al., 2025). Although GenAI can provide strong tools capable of serving the purposes of students of the ELL it is up to the student to learn how to effectively use the tools and gain real advantages. In that regard, perceptions of the students need to be understood so that a constructive intervention can be designed to promote their learning patterns.

The recent research confirms that AI has a significant part in ELL; AI is capable of adjusting to the needs of individual learners, provide them with individual feedback, and consolidate vocabulary, pronunciation, and writing skills (Alqaed, 2024; Ricart, 2024). Such mechanisms also enhance independent learning and strengthen the self-confidence of the learners in English practice (Kohnke et al., 2025; López-Minotta et al., 2025). However, the success of the AI adoption depends on the digital skills of the teachers and the readiness of students to use these devices in a responsible way (Polakova & Ivenz, 2024; Polakova & Klimova, 2024). At the same time, teachers’ perceptions and attitudes toward these technologies play a key role in shaping their pedagogical impact (Bottiglieri et al., 2025). Therefore, the pedagogical influence of AI in ELL will not happen only due to the adaptive and supportive nature of the latter, but rather the level to which educators and learners are prepared to utilize those sources efficiently and in a morally responsible way.

In line with the necessity to examine the perception and adoption of AI in the context of local environments, Aguilar-Cruz & Salas-Pilco (2025) also performed one of the limited studies on the matter in Colombia. The authors investigated the K-12 educators in Florencia, Caquetá, with the discussion of technology access, teacher training, and ethical issues. They found that teachers appreciated AI because of instructional resources development, though they were concerned about their personal skill levels in using AI, inequality in access to such resources, and the ethical concerns. Though the focus of the study was on teachers, its results can be generalized, since the realization of the lack of preparation by the teacher can suggest the possibility that students are on their own exploring AI tools without proper supervision or guidance.

Students’ Perceptions

In education, perception is defined as interpretations and appraisals of learning experiences by learners, which are structured by cognitive, affective and contextual factors and not only by their sensory processes. In the learning contexts, the perception of students is directly connected with the ideas of beliefs, attitudes, expectations and previous experiences that contribute to the way students’ approach and assess learning situations. Educational research and technology adoption studies note that the perceptual aspects are considered to be influential in motivation and reaction of learners towards pedagogical settings and technologies (Schunk, 2012; Acosta-Enríquez et al., 2024).

The importance of perception in this study lies in its well-established power to influence behavior and outcomes. Davis (1989) claims that an individual behavioral intention is determined by two perceptual factors. He called these factors (1) perceived usefulness and (2) perceived ease of use. Consequently, in ELL, this translates to whether students perceive AI tools effectively to improve language proficiency (usefulness) and whether they are intuitive and easy to interact with (ease of use).

Overall, students’ perceptions are not guided by an independent process; instead, the students are influenced by the external influence and their past exposure to technology tools. According to this paper, some of the respondents cited the recommendations of peers and prior exposure to digital platforms as the reasons that assisted them in their early experience with AI-based tools. This observation relates with the importance of social influence as it is advanced in the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology, in which users’ perceptions and intentions are determined by their social context and their previous experience with technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In this way, suggestions and previous experience with digital tools can strongly influence how students perceive AI tools for ELL. Kessler (2018) explains that when learners have a good opinion about a tool, they usually accept it faster, participate more, and feel more motivated, so, perceptions affect how students learn a language. For this reason, studying how AI is perceived in ELL includes looking at how this technology becomes part of daily learning, both inside and outside the classroom.

Methodology

The research design adopted in this study is a convergent mixed-method case study conducted as an exploratory investigation. According to Creswell (2012), convergent mixed-method designs involve the concurrent collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, which are then integrated to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research problem. The quantitative measures used in the current investigation gave the general idea of the trends of AI use and attitudinal orientation of students and qualitative narratives gave more data about students’ own experiences, reasons, and issues faced. This integrative method has enabled triangulation and validation of the results which allowed a deeper and more contextualized interpretation of the empirical results.

Participants

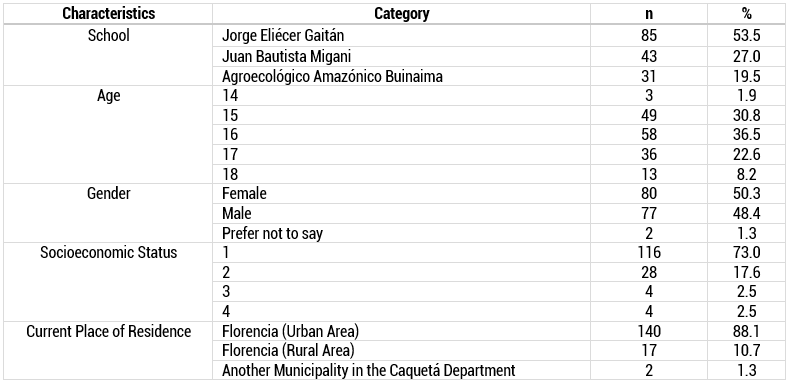

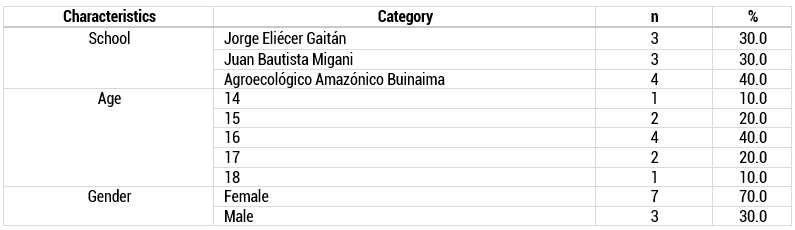

The study was conducted with 10th-grade students from three public schools in Florencia, Caquetá: Jorge Eliécer Gaitán School, Juan Bautista Migani School, and Agroecológico Amazónico Buinaima School. These institutions were selected through convenience sampling, as their administrative and teaching staff expressed interest in the project and provided full support for the data collection process. In total, 159 students participated in the survey (see Table 1), while 10 students were selected through voluntary participation to take part in the semi-structured interviews (see Table 2) to provide more detailed accounts of their experiences.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Information of Survey Participants

Note. Own elaboration.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Information of Interview Participants

Note. Own elaboration.

Data collection instruments

Two instruments were used to collect data for this study: a survey and a semi-structured interview. The survey was adapted from previously validated instruments developed by Aguilar-Cruz & Salas-Pilco (2025) and Vera (2023). The adaptation process involved contextual and linguistic adjustments to ensure relevance to the participants’ educational level and local context. In addition, to establish content validity, the adapted survey was reviewed by two experts in EFL, after that, minor modifications were made based on their feedback. Hence, our survey was designed to gather quantitative data from 10th-grade students in public schools of Florencia, Caquetá. It consisted of three sections: (1) general information, including age, gender, and socioeconomic status; (2) general perceptions of AI, perceptions and experiences related to the use of AI in ELL; and (3) expectations toward teachers’ integration of AI tools in English classes. The items combined multiple-choice questions, Likert scale statements, and open-ended responses to capture students’ knowledge, usage patterns, perceived benefits, and challenges when using AI.

A sub-group of students was given semi-structured interviews to be able to acquire qualitative information about their conceptualization and their practical experiences with AI in their processes of ELL. The interview consisted of five guiding questions that related to how students define AI, how they saw it useful to ELL, the most commonly used tools, the examples of typical tasks that students use with the help of AI, and the main challenges they faced when using these technologies. Together, these means helped obtain a complex view of the perceptions and practices of students, which allowed triangulation and more subtle data interpretation.

Data analysis

The analysis was conducted in accordance with the conceptualization of triangulation suggested by Creswell (2012), according to which the results of surveys, interviews, and available literature were methodically compared. The data collected in the surveys were analyzed through the descriptive statistics to systematize and summarize the responses, thus explaining any overall trends. With the interview data, the sequential coding methodology was used; the first stage was open coding that segmented responses to discrete units in order to discover distinguishing ideas; the second step was the axial coding that stratified the ideas into general categories; the third step was selective coding, which relates the categories to determine the dominant themes of the research. This repetitive process produced a deeper insight into the results of the research.

Ethical Considerations

Before starting the data collection process, three schools in which the research was to be conducted consented to the study on 10th-grade students. The purpose and procedures of the study were given to all the participants confidentially and their participation was optional. Every student, along with his or her parents or legal guardians, submitted the informed consent form provided by the schools and also signed another consent form, which was prepared by the researchers to be sure that rights and participation was fully understood. This protocol was carried out to guarantee the adherence to the principles of ethical research in the case of minors and protect the privacy and autonomy of the participants.

Findings and Discussion

The given section describes and analyses the main results obtained during the survey and semi-structured interviews with 10th-grade students of three state schools in Florencia, Caquetá. Findings are arranged in quantitative and qualitative elements as a way of coming up with a comprehensive understanding of how students perceive AI as a learning tool used in ELL.

General Student Knowledge and Use of AI

The first group of results explores the level of knowledge and usage of AI tools among students, based on the assumption that the knowledge of AI is the precursor of readiness to adopt these technologies in ELL.

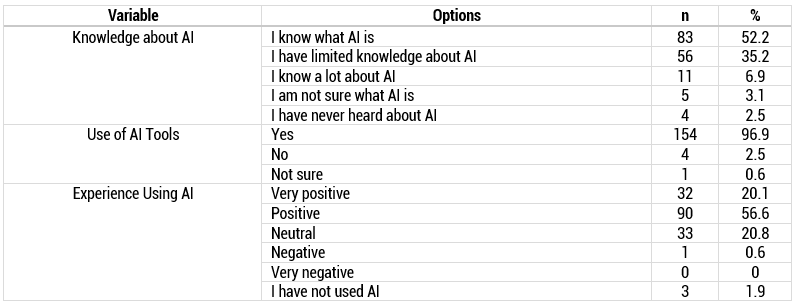

Table 3.

Knowledge and Use of Artificial Intelligence

Note. Own elaboration.

The statistics show that 96.9% of the interviewees had used at least one AI tool, with 56.6% having a positive experience (see Table 3). Such a high level of utilization implies that 10th-grade students in Florencia already know about AI technologies and are already integrating them into daily learning processes. In addition, 52.2% of students said they were aware of what AI is, compared to 35.2% only mentioned they do not know much about such tools, which also indicates a rather widespread awareness among adolescents in this situation.

These findings are in line with the growing world trend of using AI among younger readers. Alqaed (2024) also reported similar patterns in Saudi Arabia, where the majority of secondary students had the knowledge of AI and used it to aid their ELL with the help of translation, grammar-checking, and vocabulary tools. The high usage seen herein could thus be the reflection of the rising availability of AI through mobile applications as well as social media platforms that has broken the boundary between formal and informal learning sites. Moreover, the positive attitudes, which were observed between students in Florencia, find an echo in Kohnke et al. (2025), who discovered that students see generative AI tools as useful in personalized English practice and language production. The authors underline that the ability of AI to give instant feedback, increase autonomy, and self-paced learning is appreciated by learners, which explains why more than a half of the Colombian students claimed the positive experience. However, the results also show that 35.2 % of students keep only partial information about AI, which demonstrates the presence of unequal distribution of digital literacy. Polakova & Ivenz (2024) have also reported that students do not have a comprehensive understanding of the operation of AI tools and the way they can successfully make use of them even though the access to these tools has been increased.

This implies that there is a necessity of the explicit pedagogical mediation, whereby the instructors do not only teach learners the operative elements of AI, but also motivate the learners in terms of when and why to use such tools. Surprisingly, even though 96.9% of students claimed to have used AI, merely 6.9% of them indicated that they had an in-depth knowledge about it, which suggests that utilization is not necessarily equal to a profound understanding of AI. This disparity between application and insight is consistent with Peña-Acuña & Durão (2024) who found that most future educators and students use AI-based tools intuitively without necessarily understanding how they work or what their shortcomings are.

These results emphasize the need to consider AI literacy, including technical and critical consciousness, so that students are able to use these technologies in a responsible and meaningful way. Lastly, the overwhelming number of positive reports and the lack of negative ones (only 0.6%) indicate a positive environment in which AI can be incorporated into ELL. Nevertheless, to successfully introduce AI into education, as Aguilar-Cruz & Salas-Pilco (2025) argue, the access and attitudes alone are not enough because the implementation process depends on the readiness of teachers and ethical issues. As a result, the current state of students in Florencia seems to be permissive and willing to work with AI, but their efficient and sustainable use will need pedagogical assistance and digital education.

Students’ perceptions of AI in ELL

This part investigates the perceptions of students about the AI as applied in ELL. These statistics are critical in building a comprehensive picture of the attitudes, motivation, and concerns of learners with the use of AI in ELL.

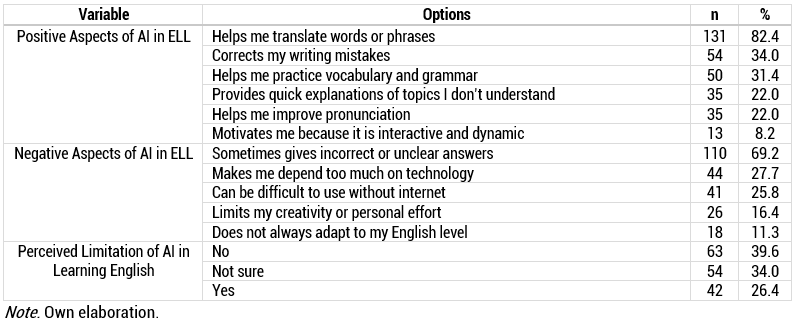

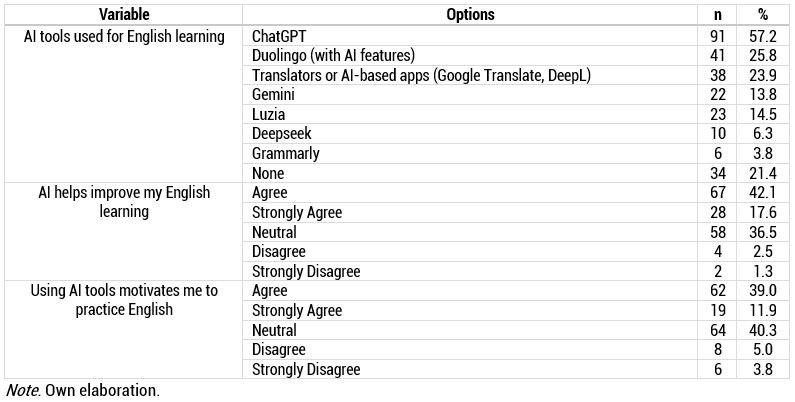

Table 4.

Students’ perceptions of AI in ELL.

According to Table 4, a significant majority of students (82.4%) indicated the use of AI as a tool to translate words or phrases, followed by those who use it as a tool to correct writing mistakes (34%) and to train grammar and vocabulary (31.4%). The fact that translation was predominantly identified by students as a perceived advantage suggests a functional but potentially uncritical use of AI translators. This finding can be interpreted through Bowker’s (2021) argument that machine translation literacy is necessary for learners to engage critically with AI translation tools and to become aware of their limitations and potential language biases.

Additionally, our results also indicate that students mostly see AI as a useful, language-support tool and not as a creative or interactive companion. These findings are consistent with the study by Alqaed (2024), which recorded that Saudi ELL students use AI primarily to translate texts and receive grammatical advice instead of to practice writing, and with the analysis of how ChatGPT could help in improving written expression in English learning through facilitating linguistic accuracy and learner autonomy. Therefore, AI seems to be seen mostly as a supportive tool that enhances the mechanical side of ELL.

Moreover, the data also show that 22% of respondents use AI to explain things or enhance pronunciation, and 8.2% of users are also motivated by its interactivity and dynamism. These trends are reflective of the findings of Kohnke (2024) & Kohnke et al. (2025), in which learners prioritized the immediacy and personalization of AI technologies, especially when the self-confidence is built through the use of instant feedback. Additionally, López-Minotta et al. (2025) revealed that AI-based systems provide rich oral expressiveness through the opportunities of flexibly practicing, which helps to reduce anxiety and increase engagement. All these findings point to the fact that AI not only adds to the cognitive dimension of learning but also to the affective one, thus encouraging students to practice independently.

However, learners also found serious impediments. Most of the respondents (69.2%) stated that AI would sometimes give wrong or vague responses, and about a quarter of them expressed an apprehension about excessive reliance on technology (27.7%) and internet addiction (25.8%). The issues bring up parallels to the cautions by Muñoz et al. (2025) regarding the risk of poor quality of learning and academic dishonesty when inaccuracies and blind use of generative AI, like ChatGPT, are used. Moreover, 16.4 % have indicated that AI restricts the process of creativity or individual effort, which can also be supported by Dwivedi et al. (2023), who state that generative systems can assist in creating intellectual apathy without proper teacher assistance. Interestingly, 39.6% of students did not feel AI limited their ELL, even though 34% were unsure, possibly due to a transition period in AI literacy where students are aware of its benefits but do not have the critical awareness of its dangers.

Table 5.

Use of AI Tools in ELL

As shown in Table 5, most students (57.2% of them) reported using ChatGPT as the main tool in ELL, after which came Duolingo (25.8% of those) and AI-based translators (Google Translate or DeepL) (23.9% of them). This ChatGPT dominance is an indication that the generative conversational models have quickly found their way into the learning ecosystem of students. Similarly, Kohnke et al. (2023) found that participants use ChatGPT to translate, check their grammar, and ideate and appreciate its conversational and responsive quality.

On the perceived impact, 59.7% of students agreed or strongly agreed that AI helped them to develop the English language and 50.9% of students stated that they were more motivated to practice when they received AI tools. This affirmative position is in line with the results of Polakova & Ivenz (2024), who report that AI feedback tools promote writing accuracy and writing motivation among learners and that AI increases student engagement because it makes the learning experience more personal and instant. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) can also be used to explain the motivational potential that can be seen among the students. The participants also emphasized that AI tools were most interesting when they were viewed as useful in academic work and easy to operate, in particular, in the quick feedback provision and language practice assistance. These perceptions are consistent with the fundamental aspects of TAM, which are the perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use (Davis, 1989) which have been considered as key factors that influence acceptance of new technologies being adopted by users (Venkatesh et al., 2003). To this end, the satisfaction and motivation of students would probably be based on the immediate assistance and perceived gains that AI provides in the process of learning.

Additional qualitative evidence points to the fact that students see AI as an educational support and a stimulating force, but at the same time, they recognize the need to mediate and critically use it through the teacher. They support the availability of AI and its urgency, but they are aware of its limitations, especially on precision and trustworthiness (see Table 6).

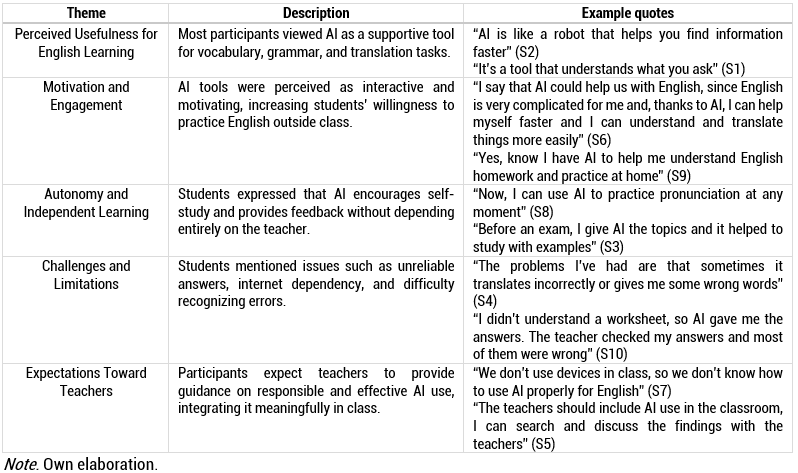

Table 6.

Emerging Categories from Students’ Semi-Structured Interviews on the Use of AI in ELL

Table 6 suggests that students always stated that AI is a helpful tool to use when developing vocabulary, correcting grammar, and translating. The claim that AI is a robot that helps you find information faster is a manifestation of a functional and instrumental view of AI, which is also common among learners, as reported by Alqaed (2024) and Polakova & Klimova (2024), who discovered that simplifying linguistic tasks is the priority of AI. This image implies that AI is linked by students with effectiveness and academic support instead of more profound communication.

Students’ Expectations Regarding Teachers’ Integration of AI in ELL

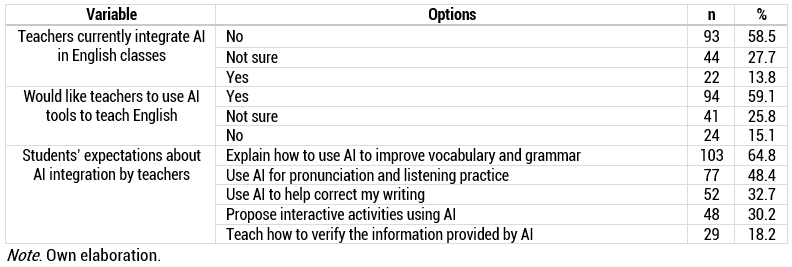

The expectations of students on the integration of AI in ELL can be the valuable insights to understand how the students imagine the balance of human and technological mediation by teachers. The results provided in Table 7 show that students have high awareness of the potential of AI, but they also consider teachers as the important mediators in assisting them to apply these tools in purposeful, ethical and effective way.

Table 7.

Students’ Expectations Toward Teachers’ Integration of AI in ELL

The data indicate that 58.5% of students said that AI is yet to be implemented in their English classes and only 13.8% said that it is used by teachers at the moment. Meanwhile, most (59.1%) of them said they would like to see teachers use AI tools in teaching. Such findings indicate that there is a vivid disparity between the increasing use of AI by students outside of school and its minimal use in classrooms. This trend can be explained by Talan (2021) as a pedagogical lag in the implementation of AI, in which institutional preparedness and teacher training have not been as dynamic as technological innovation. In a similar study, Umpiérrez Oroño et al. (2025) had found out that even though the use of AI tools is common among university students in Uruguay, it is not formally integrated into the curriculum because of the lack of digital infrastructure and teacher training.

The expectations of students also highlight their aspiration to have facilitated and practical learning with AI. Most (64.8%) of the teachers expected AI to be used to help students gain vocabulary and grammar, and almost half (48.4%) wanted AI to be used to enhance their pronunciation and listening exercises. This observation is also similar to López-Minotta et al. (2025), who have shown that the application of AI-based systems has a strong positive influence on the oral expression development of students as it provides them with constant pronunciation feedback and allows them to engage in verbal communication. Such preferences can be supported by Peña-Acuña & Durão (2024) because they indicated that pre-service teachers believe AI to be particularly helpful in supporting linguistic accuracy and understanding by engaging with interactive activities and pronunciation feedback. These expectations can also be interpreted as the learners realizing the potential of AI as a formative and adaptive tool, as was the case with Hwang et al. (2020), who are focused on the ability of AI to offer personalization of language learning based on the analysis of the learner input and the following modification of practice.

A smaller but also significant percentage of students (32.7%) in our study predicted that teachers would use AI to correct writing, and 30.2% proposed the application of AI in interactive classroom activities. The results indicate that learners consider AI as a source of feedback and as an agent of active learning processes. Ivanova et al. (2024) also report that students are more active when AI is applied to support collaborative and creative assignments by educators instead of as an assessment method. Their study highlights that the pedagogical usefulness of AI lies in the way in which the teachers organize the interactional learning processes that encourage engagement and innovation.

Besides this, we established that 18.2% of students wanted their teachers to educate them on how to fact-check the information given by AI and this indicates a growing realization that there was a need to be both digital and critical literate. This is one of the anxieties that both Wang et al. (2024) suggest regarding AI literacy, because students and teachers need to learn how to critically assess AI-generated content to prevent false information and dependence. Similarly, Hwang et al. (2020) emphasize that creating ethical and critical competencies is imperative to make sure that AI becomes an augmenter of human intelligence and not a replacement of it.

Combined, these results help to understand that students expect teachers to have a complex role: they should act as teachers of technology, language, and moral teachers. Although learners value the effectiveness and flexibility of AI, they still depend on teachers to make the learning process more contextual and human and justify it. This is similar to Peña-Acuña & Durão (2024) and Ivanova et al. (2024), who state that the future of AI-enhanced education is in the pedagogically competent teachers who can employ AI in the communicative, reflective, and human-centered learning environments.

These results also indicate more general institutional and policy issues that determine the implementation of AI in schools. According to Ruiz & Gallagher (2025), a rural-urban digital divide in which infrastructures and professional development opportunities are disproportionate continues to be visible in national and regional education policy in Colombia. The existence of this inequality directly influences how teachers can address the expectations of students as far as AI is used in the classroom. In this regard, previous research has shown that despite the new AI technologies, the institutional support mechanisms and methodical teacher training are lacking in most education systems to enable such AI classrooms to be operated (Aguilar-Cruz & Salas-Pilco, 2025; An & Park, 2026). Such gaps should be filled to facilitate the attainment of a balance between the expectations of the students towards AI-aided learning and teaching, as well as the willingness of the teachers to integrate AI in teaching, the commitment of the institution to leverage the opportunities of technology, and equity in accessing such opportunities.

Conclusions

The researchers discovered that most of the tenth-grade students in Florencia are already conversant with and actively use the AI tools in ELL. Their theoretical proficiency, nonetheless, is more of a performative than an analytical one as most of them engage with AI intuitively, without having a thorough perspective of the mechanisms driving it. This implies that although the students are interacting online, there is still the necessity of teaching methods that can promote AI literacy and critical awareness. The popularity of the use of AI, like ChatGPT, Duolingo, and Google Translate, shows that AI already infiltrates the informal learning process of students, helping them learn vocabulary, learn grammar, and train translation skills outside the classroom environment.

It is concluded that students view AI as a helpful partner in their ELL pursuits, as it first and foremost provides instant feedback, personalized practice opportunity, and the feeling of autonomy. They value speed of accessing explanations and having the ability to practice on their own which increases self-confidence and motivation. However, they are aware of the significant weaknesses such as inaccuracies in answers, reliance on internet connection, and chances of overdependence on technology. These results are indicative of a compromise between excitement and caution, which proves that learners are just starting to realize the pedagogical potential as well as the ethical implications of language learning mediated by AI.

Besides, the research concludes that students made clear statements about the role of teachers in integrating AI into the classroom. They expect the teachers to not just use such tools as language drills but also educate them on proper and critical use. It means that the learners regard teachers as the inseparable mediators who can connect technological material with meaningful learning experiences. The statistics also imply that although students apply AI in non-formal education, they still prefer to have human instructions to make sure that these means are implemented in pedagogically reasonable fashion that would help to develop creativity and in-depth knowledge.

All in all, the results support the importance of further incorporation of AI literacy and critical pedagogical models into the teaching of English, particularly in public schools where technology and professional growth opportunities may be limited. Further studies should explore how the perceptions of teachers and their degree of readiness affect the experience of AI among students and how AI allows facilitating not only linguistic competence but also cultural and ethical reflection. Increasing the sample to other areas could shed light on the connection between socioeconomic and geographic factors and the relationship between students and AI in language learning.

Limitations

This study presents certain limitations that should be considered. First, the research involved a limited number of participants, as data were collected only from public schools that expressed interest and willingness to participate, which restricted the inclusion of a larger or more diverse sample. Second, the study relied exclusively on individual self-reported perceptions; we consider that the incorporation of additional qualitative techniques, such as focus groups, could have generated richer insights by allowing students to collectively reflect on their experiences and learn from the perspectives of their peers. Finally, from a methodological standpoint, the research process was designed as a case study, which prioritizes in-depth understanding over broad generalization. That means, we acknowledge that future research could adopt intervention-based or alternative methodological approaches to further explore how students’ perceptions of AI in ELL develop through structured and sustained pedagogical experiences.

Bibliographic references

Acosta-Enríquez, B. G., Reyes-Pérez, M. D., Huamani Jordan, O., Carreño Saucedo, L., Padilla-Caballero, J. E. A., Fernández-Alnkairano, A. E. F., … Alarcón Bustíos, J. M. (2025). Exploring the determinants of the sustainable use of artificial intelligence in Peruvian university teachers: A structural equation modeling analysis. Sustainability, 17(7), 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072834

Acosta-Enríquez, B. G., Ramos Farroñán, E. V., Villena Zapata, L. I., Mogollon Garcia, F. S., Rabanal-León, H. C., Morales Angaspilco, J. E., & Saldaña Bocanegra, J. C. S. (2024). Acceptance of artificial intelligence in university contexts: A conceptual analysis based on UTAUT2 theory. Heliyon, 10(19), e38315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38315

Aguilar-Cruz, P. J., & Salas-Pilco, S. Z. (2025). Teachers’ perceptions of artificial intelligence in Colombia: AI technological access, AI teacher professional development and AI ethical awareness. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 34(2), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2025.2451865

Alqaed, M. A. (2024). AI in English language learning: Saudi learners’ perspectives and usage. Advanced Education, 2024(25), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.20535/2410-8286.318972

An, H., & Park, M. (2026). AI tools and fashion design education: Instructor perspectives on student challenges and design process tool support. Fashion and Textiles, 13(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-025-00452-9

Andrade-Girón, D., Marín-Rodríguez, W., Sandivar-Rosas, J., Carreño-Cisneros, E., Susanibar-Ramirez, E., Zuñiga-Rojas, M., & Ángeles-Morales, J. (2025). Generative artificial intelligence in higher education learning: A review based on academic databases. Iberoamerican Journal of Science Measurement and Communication, 4(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.47909/ijsmc.101

Arbulú Ballesteros, M. A., Acosta Enríquez, B. G., Ramos Farroñán, E. V., García Juárez, H. D., Cruz Salinas, L. E., Blas Sánchez, J. E., ... & Farfán Chilicaus, G. C. (2024). The sustainable integration of AI in higher education: Analyzing ChatGPT acceptance factors through an extended UTAUT2 framework in Peruvian universities. Sustainability, 16(23), 10707. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310707

Atencio-González, W. J., & Criollo-Ñato, A. E. (2025). The influence of artificial intelligence on learning English as a second language among Ecuadorian students. Cognopolis: Revista de Educación y Pedagogía, 47, 78. https://doi.org/10.62574/v47qnv78

Bottiglieri, L. I., Irrazabal, M. F., & Ramallo, C. (2025). Educators in transition: Unpacking Argentinean teachers’ attitudes towards AI in higher education. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.355874

Bowker, L. (2021). Promoting linguistic diversity and inclusion: Incorporating machine translation literacy into information literacy instruction for undergraduate students. The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion, 5(3), 127–151. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48644449

Cabrera-Solano, P., Ochoa-Cueva, C., & Castillo-Cuesta, L. (2025). Enhancing EFL higher education through Fliki videos: An artificial intelligence implementation approach. World Journal of English Language, 15(1), 424–443. https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v15n1p424

Caiza, G., Villafuerte, C., & Guanuche, A. (2025). Interactive Application with Virtual Reality and Artificial Intelligence for Improving Pronunciation in English Learning. Applied Sciences, 15(17), 9270. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15179270

Castillo-Cuesta, L., Ochoa-Cueva, C., & Cabrera-Solano, P. (2025). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of the use of artificial intelligence in an English as a foreign language learning context. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 24(10), 818–841. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.24.10.39

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational Research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantiative and qualitative research. PEARSON.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

De La Torre, A., & Baldeón-Calisto, M. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence in Latin American higher education: A systematic literature review. In A. Varol, M. Karabatak, C. Varol, & E. Tuba (Eds.), 2024 12th International Symposium on Digital Forensics and Security (ISDFS) (pp. 1–7). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISDFS60797.2024.10527283

Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., Baabdullah, A. M., Koohang, A., Raghavan, V., Ahuja, M., Albanna, H., Albashrawi, M. A., Al-Busaidi, A. S., Balakrishnan, J., Barlette, Y., Basu, S., Bose, I., Brooks, L., Buhalis, D., … Wright, R. (2023). Opinion paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642

Guanuche, A., Paucar, W., Oñate, W., & Caiza, G. (2025). Immersive Haptic Technology to Support English Language Learning Based on Metacognitive Strategies. Applied Sciences, 15(2), 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15020665

Hwang, G.-J., Xie, H., Wah, B. W., & Gašević, D. (2020). Vision, challenges, roles and research issues of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1, 100001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2020.100001

Insuasty, A., Velásquez Villarreal, D., & Hernandez Burgos, M. (2025). Revolutionizing language learning: The impact of AI in EFL education. Journal of English Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics, 7(6), 01–08. https://doi.org/10.32996/jeltal.2025.7.6.1

Ivanova, M., Grosseck, G., & Holotescu, C. (2024). Unveiling insights: A bibliometric analysis of artificial intelligence in teaching. Informatics, 11(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics11010010

Kessler, G. (2018). Technology and the future of language teaching. Foreign Language Annals, 51(1), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12318

Kohnke, L. (2024). Exploring EAP students’ perceptions of GenAI and traditional grammar-checking tools for language learning. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100279

Kohnke, L., Moorhouse, B. L., & Zou, D. (2023). ChatGPT for language teaching and learning. RELC Journal, 54(2), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882231162868

Kohnke, L., Zou, D., & Su, F. (2025). Exploring the potential of GenAI for personalised English teaching: Learners’ experiences and perceptions. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8, 100371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2025.100371

López-Minotta, K. L., Chiappe, A., & Mella-Norambuena, J. (2025). Implementation of artificial intelligence to improve English oral expression. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 15(1), 43–71. https://doi.org/10.17583/remie.16188

Muñoz, B. C., Nassaji, H., & Bello Carrillo, F. I. (2025). ChatGPT-generated versus human direct corrective feedback on L2 writing. System, 134, 103805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2025.103805

Nelson, A. S., Santamaría, P. V., Javens, J. S., & Ricaurte, M. (2025). Students’ perceptions of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) use in academic writing in English as a foreign language. Education Sciences, 15(5), 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050611

Peña-Acuña, B., & Durão, R. C. F. (2024). Learning English as a second language with artificial intelligence for prospective teachers: A systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1490067

Polakova, P., & Ivenz, P. (2024). The impact of ChatGPT feedback on the development of EFL students’ writing skills. Cogent Education, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2024.2410101

Polakova, P., & Klimova, B. (2024). Implementation of AI-driven technology into education: A pilot study on the use of chatbots in foreign language learning. Cogent Education, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2024.2355385

Ricart, A. (2024). ChatGPT como herramienta para mejorar la expresión escrita en inglés como lengua extranjera. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 29(2). https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.354584

Robayo-Pinzón, O., Rojas-Berrio, S., Rincón-Novoa, J., & Ramírez-Barrera, A. (2023). Artificial intelligence and the value co-creation process in higher education institutions. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 40(20), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2259722

Rojas-Paucar, W., Chávez-Garcés, E. M., Rodríguez Chávez, D. A., & Cueva Ancalla, H. (2025). Teaching perceptions and experiences in the use of generative artificial intelligence in higher education. Scientific Research Journal CIDI, 6(10), 22–37. https://srjournalcidi.org/index.php/ojs/article/view/258

Ruiz, N., & Gallagher, M. (2025). Rural education imaginaries in digital education policy: An analysis of CONPES 3988 in Colombia. International Journal of Educational Development, 113, 103222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2025.103222

Schunk, D. H. (2012). Learning theories: An educational perspective (6th ed.). Pearson.

Talan, T. (2021). Artificial intelligence in education: A bibliometric study. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 7(3), 822–837. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijres.2409

Umpiérrez Oroño, S., Pérez Rodríguez, B., & Cabrera Borges, C. A. (2025). Uso de inteligencia artificial en estudiantes de enseñanza superior uruguaya. Educación y Educadores, 27(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.5294/edu.2024.27.3.2

Vargas Bernuy, J. B., Nolasco-Mamani, M. A., Velásquez Rodríguez, N. C., Gambetta Quelopana, R. L., Martinez Valdivia, A. N., & Espinoza Vidaurre, S. M. (2025). Relative advantage and compatibility as drivers of ChatGPT adoption in Latin American higher education: A PLS-SEM study towards sustainable digital education. Sustainability, 17(18), 8329. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188329

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M., Davis, G., & Davis, F. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

Vera, F. (2023). Faculty members’ perceptions of artificial intelligence in higher education: A comprehensive study. Transformar, 4(3), 55–68. https://revistatransformar.cl/index.php/transformar/article/view/103

Wang, S., Wang, F., Zhu, Z., Wang, J., Tran, T., & Du, Z. (2024). Artificial intelligence in education: A systematic literature review. Expert Systems with Applications, 252, 124167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124167

Zambrano Rodriguez, L. B., San Lucas Marcillo, S. M., & Loor Párraga, A. C. (2025). Chatbots and vocabulary learning: Perceptions from EFL university students. UNESUM – Ciencias. Revista Científica Multidisciplinaria, 9(3), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.47230/unesum-ciencias.v9.n3.2025.176-185

Este artículo no presenta ningún conflicto de intereses. Este artículo está bajo la licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0). Se permite la reproducción, distribución y comunicación pública de la obra, así como la creación de obras derivadas, siempre que se cite la fuente original.